Book Project

Dominant theories of political transitions and redistribution suggest that negotiated settlements involve a trade-off: elites concede political incorporation to opposition actors yet resist wealth redistribution—especially when wealth is tied to land. Contrary to these expectations, 40 of 79 peace settlements addressed land reform between 1991 and 2022 (PA-X dataset, University of Edinburgh). Under what conditions is land redistribution achieved in civil war political transitions? More specifically, why is land redistribution enshrined in peace settlements? Why is it implemented at varying degrees?

I develop a theory of unarmed opposition mobilization—that is, non-elite, civilian collective action—to explain both the negotiation of redistributive commitments and land delivery to the rural poor in civil war peace processes. I argue that rural social movements—who are often at the forefront of unarmed mobilization and directly affected by dispossession—shape redistribution when they deploy mobilization strength: the ability to engage in intense political contention—organizational capacity—and credibly assert autonomy from warring factions—distancing capacity.

I offer a two-staged argument. At the negotiation phase, I theorize two strategic forms of collective action through which rural movements shape redistributive commitments. Where insurgents set the agenda, movements align their land claims with insurgents’ negotiating stance and pressure the government into commitment. In this scenario, movements embark on what I term bridging mobilization—they reduce the gap between warring sides’ preferences within the war-peace dyad. In contrast, when rebels fail to set the agenda, movements build consensus for land redistribution with the government and reform-minded elites, forming a constituent coalition. In this setting, movements deploy what I call expanding mobilization—they forge alliances across partisan divides and beyond the conflict dyad.

Movements drive land allocation to the poor when they combine mobilization strength with political incorporation—that is, their formal recognition as legitimate political actors entitled to new rights and sustained access to state institutions. When both conditions are met, movements achieve systematic redistribution—or the regular delivery of property rights to dispossessed communities—by influencing policymaking from within state institutions. Absent incorporation, movements achieve only episodic land transfers to the poor—or occasional land transfers—by pressing from the margins of policymaking.

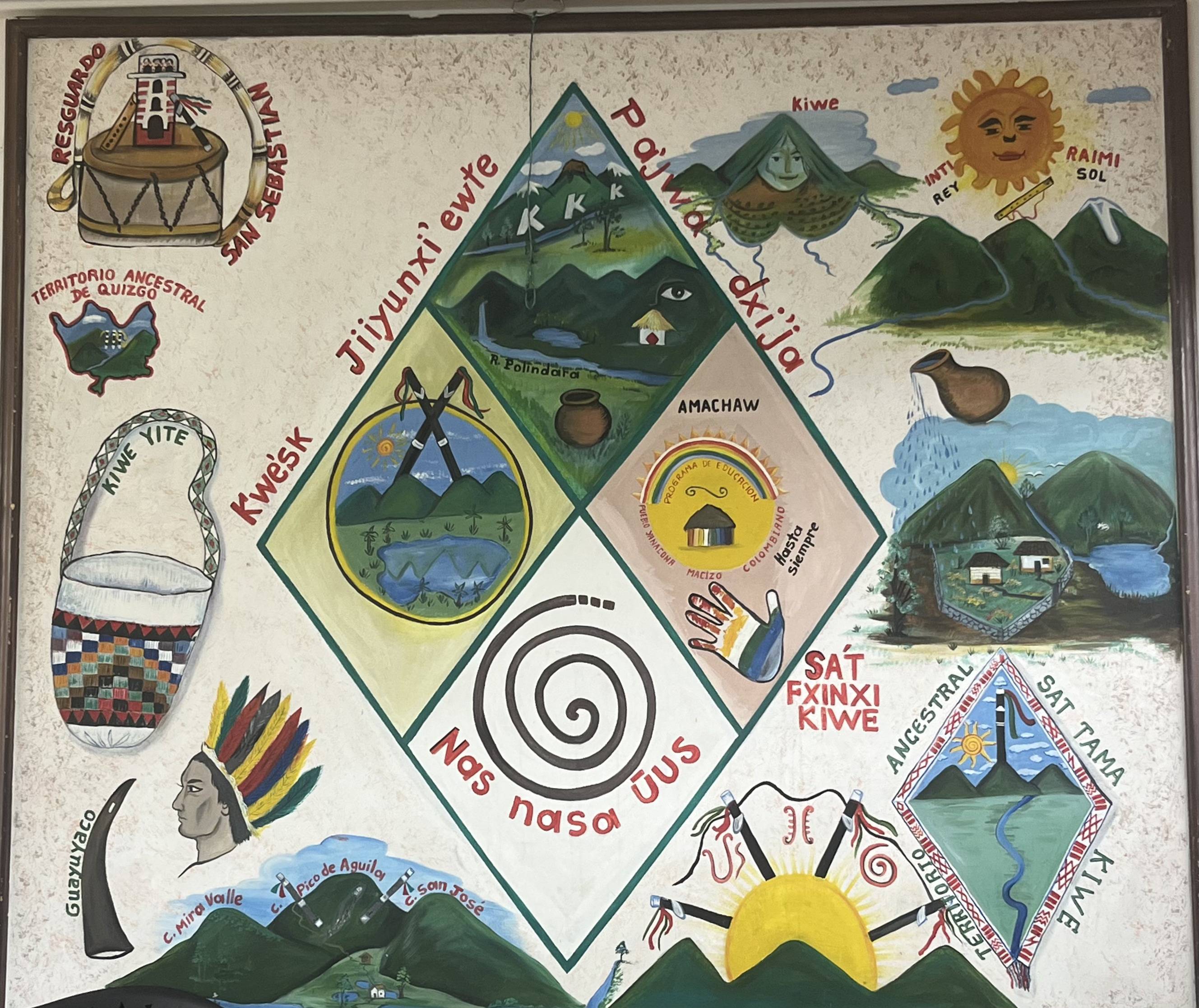

I test this theory through within-case and cross-case comparisons in Latin America, focusing on Colombia, El Salvador and Guatemala. In Part I of the book, I conduct comparative historical analysis of two peace processes (1982–1991 and 2012–2016) in Colombia—which represents a least-likely case for redistributive reform. I show that Indigenous and Afro-descendant movements secured communal land by reframing redistribution as reparations for slavery and colonialism, and participating in state institutions in the first process. In the second instance, I find that peasant movements achieved redistributive commitments yet struggled to secure land allocation until political incorporation at later implementation stages. I combine process tracing, natural language processing, and statistical modeling to trace how mobilization shaped reform commitments and to estimate its effects on land allocation across municipalities and years.

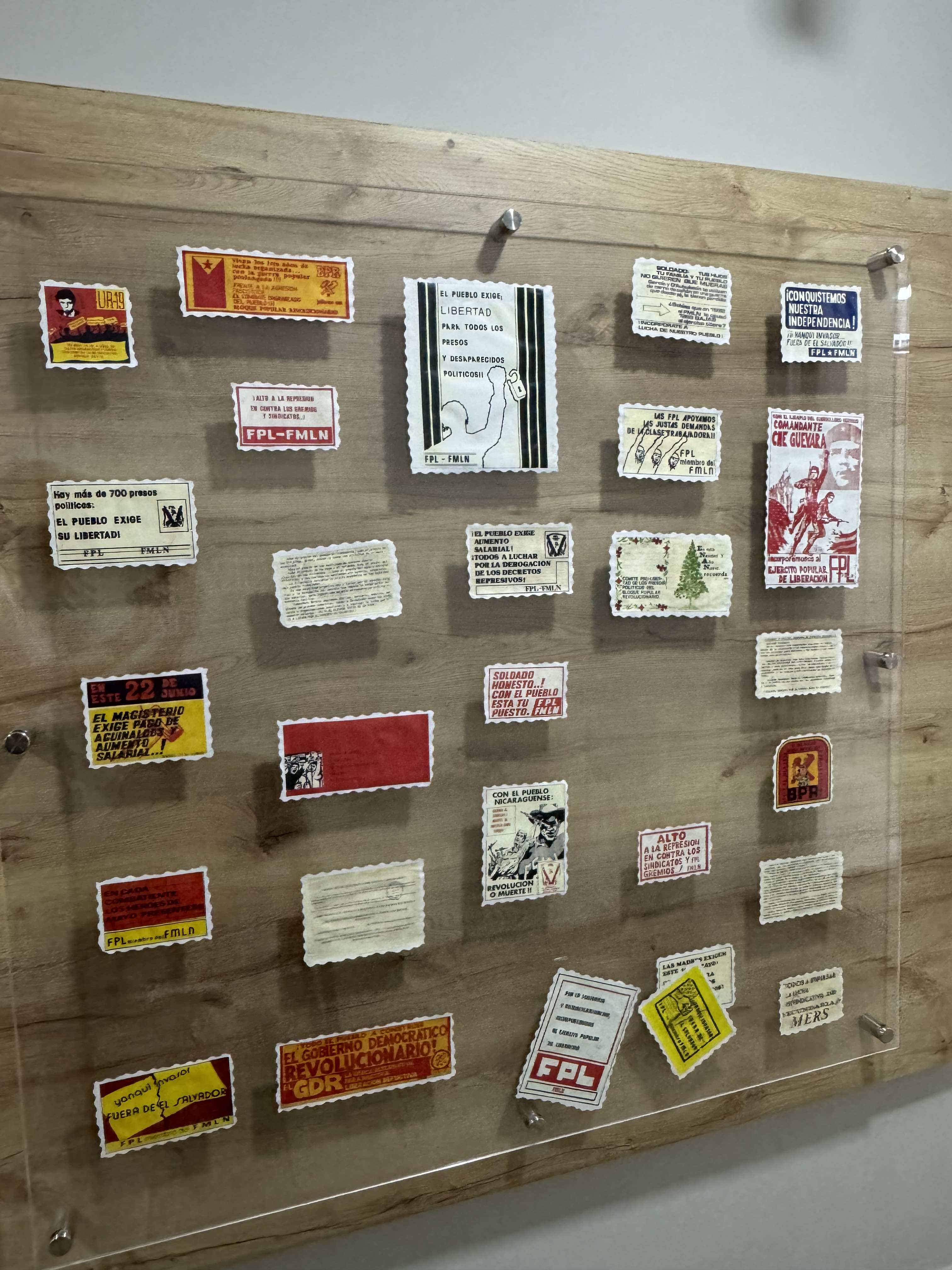

In Part II, I assess the external validity of the theory. Using cross-national analysis of peace agreements (1991–2022), I show that this pattern can be observed in civil war peace processes beyond Latin America. Through shadow case studies, I demonstrate that rural movements allied with FMLN negotiators, securing a land transfer program for demobilized fighters and landless peasants in El Salvador. In Guatemala, by contrast, Indigenous and peasant organizations exhibited limited organization capacity and failed to credibly distance themselves from politically weak insurgents. Absent a broad-based coalition, the 1996 peace agreement excluded redistributive reform and only enshrined market-based land policies. The book project draws upon data I collected over 16 months of fieldwork in Colombia and one month in Central America, including original archival materials (e.g., clandestine documents and negotiation records), participant observation, 134 in-depth interviews, novel datasets on rural mobilization and land allocation, and GIS mapping.

Fieldwork

I have conducted extensive ethnographic and archival fieldwork in Colombia, El Salvador, and Guatemala. Below, you can take a glance at my on-the-ground fieldwork experience.